Climate is is always changing, cows are too. Why heat stress abatement is even more critical

The economic impact of heat stress for American agriculture is pegged at over $4 billion per year. Globally, it exceeds $500 billion annually.

For dairy, the cost is greater than $1.7 billion/year, which does not include the negative impacts on dry cows. The losses are larger in years like 2022, when milk prices are higher and feed costs are higher.

“The impact happens sooner than we think. The climate has been changing since the beginning of time,” says animal scientist Dr. Lance Baumgard. “Globally, heat stress management is going to get worse, and cows that are more productive are more sensitive to heat stress.”

Weather patterns have been all over the map this past winter and spring – warm spells through the winter and mid-spring snowstorms to the north.

Dr. Baumgard has been studying heat stress in cattle and other livestock in various regions of the country for decades. He surprised dairy farmers attending a conference in central Pennsylvania. He shared data of cows logging body temperatures over 103 degrees F., while being “crammed together” in holding pens in the last week of December 2022 in northern Wisconsin.

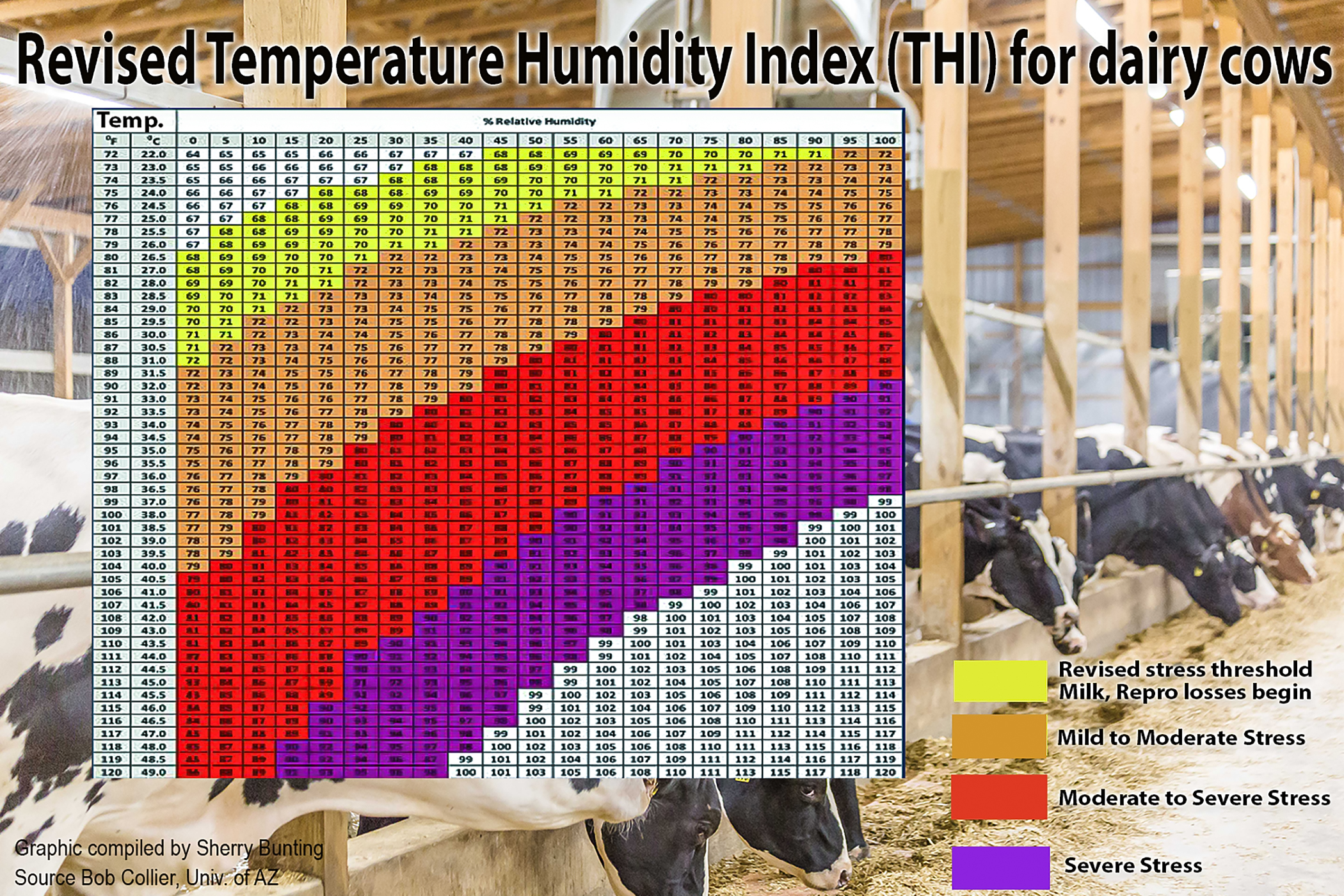

He says when it’s 95 degrees F. at 65% relative humidity in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, that’s a THI of 86, which is 14 units above the 72 threshold in the middle of the moderate heat stress range. Meanwhile, in Arizona, it can be 105 degrees F. at 10% humidity for a THI of 82 — less than here in the middle of summer.

“In a hot dry climate, cattle are able to sweat,” Baumgard explains. What happens in a humid climate is the heat stress persists even when the sun goes down, and the temperature declines because the air becomes ‘smaller’ but humidity goes up.

“When we have a 75 or 80% relative humidity, the index is high. This is why at 3:00 a.m. your cows are still heat stressed.”

Even in the northern U.S. and Canada, heat stress in cattle is becoming more prevalent due to the combination of more productive cows and a changing climate.

Farmers are rethinking the index at which modern dairy cows begin to experience heat stress and when to initiate cooling.

In fact, notes Baumgard, there’s a new first-ever climate insurance product developed in Europe and launching soon in the U.S. called Heat Stress Protect, which is designed to help dairy farmers mitigate economic losses, including milk production and quality, reproductive efficiency, cow health, energy and labor caused by extreme heat stress.

It’s fully automated using the combined temperature and humidity index (THI) and announces payouts when conditions are met.

The problem with using a 72 THI threshold for heat stress in cattle is it was developed in the 1950s.

“Today, cows make more milk and produce more heat. At a THI of 70, she’s already down 6 pounds in milk,” Baumgard stresses. “When the daily minimum THI – at the lowest time of the day – does not get below 67, she’s down 6.5 pounds. This is not the average of the day but the minimum index of the day that happens around 4:00 a.m.”

Baumgard used data to show that modern cows begin to experience heat stress at a THI of 65 to 68, which is much lower than the traditional threshold of 72.

“As milk production continues to increase, the THI at which cows become stressed will continue to decrease,” he says, adding that these indexes do not account for solar radiant, which impacts cows in the sun sooner than those under shade.

According to Baumgard, providing nighttime cooling is important in more humid climates, and even in the drier climates, except at higher elevations. The difference between New Mexico and Arizona is the higher elevation produces a nighttime drop in the temperature and index.

Visible signs of heat stress include open mouths, panting and drooling. This means the cow is losing saliva.

Heat stressed cows also choose to stand, whereas hogs will choose to lay down, he explains: “Heat stressed cattle bunch together, and no one knows why.”

Along with reduced production in cows and slower growth in youngstock, “there are other things costing you money that you may not easily recognize: reduced body condition, acute health problems, rumen acidosis (remember the signs, she is losing saliva), significant drop in pregnancy rate, increased abortion rate, and increased death loss.”

The effect on summer preg rate is compounded by pushing the calving schedule for those later-bred cows out to June or July the following year at the worst time for calving. This is one example of the cascade effect as the impact of heat stress begins to affect the herd on multiple levels.

Baumgard points out that data for North America over the last five years show that as soon as the daily THI hits 70, cows start to die 2 to 3 days after. He attributes this to the cow not being able to fight off something as easily, for example a case of mastitis.

The impact on rumen pH is a big one, he says, it affects production, components and health, and it also affects conception rates. She’s losing saliva and along with the panting, comes a loss of systemic buffering capacity.

“Dogs, cows and pigs do not sweat very well. Horses do. When cows are in an acidotic state, we see inconsistent feed intake, which makes the problem worse,” says Baumgard. “We may want to feed more energy, but be careful to avoid slug feeding. We want them to have as many meals as possible. Small but frequent.”

In addition to the inconsistent intakes affecting rumen pH, the cow is drooling. “She’s losing saliva, and that saliva is golden. It contains bicarb. She is also making less saliva,” he adds.

What else is going on?

“Respiration rate increases, causing her to exhale more carbon dioxide, which changes the ratio of carbon dioxide to bicarb in the blood, causing the kidneys to dump more bicarb into the urine to compensate. So now there’s even less bicarb to buffer the rumen.”

Baumgard suggests that adding more grain to the diet can complicate this scenario. He tested the hypothesis that milk yield declines because heat stressed cows eat less. It’s not that simple.

“We heat stressed one group and measured the reduced feed intake, and we had a control group consuming the same quantity of feed as those heat stressed cows. The heat stressed cows continued to go down in milk while the thermo-neutral group – eating the same amount of feed as the heat stressed cows – after adjusting, maintained their milk production,” he explains.

In other words, all of that continued loss in production in the heat stressed group had nothing to do with the feed intake. “If the herd is down 6 pounds, 3 is from reduced feed intake and 3 is from something else.”

Discussing some of the biochemistry angles, he notes that heat stressed cows secrete less glucose, and milk yield is dependent on glucose. Where is it going?

“The liver is making it but the mammary gland is not using it,” says Baumgard. “There’s a diversion of blood to the skin and extremities to help with dissipating heat. Vasoconstriction in the intestinal tissues also reduces nutrient and oxygen uptake and delivery. The destruction to intestinal cells can be massive – like a bomb went off, and now we have antigens and microbes getting into the cow, not staying in the gut, and now we have an immune response. It happens rapidly.”

He compares what is seen in a blood test from heat stressed cows to what is seen in a systemically ill mastitis cow. “She’s sick and prioritizing survival.”

Baumgard stresses the importance of modifying the cow’s environment to reduce the negative consequences of heat stress. (See part one.)

By Sherry Bunting

-30-